|

UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, Army and draft resisters, No-Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. The Suyama Project is made possible through the generous gift of an anonymous donor who wanted to honor and remember the legacy of resistance, broadly understood. |

Category Archives: Riots/Unrest TULE LAKE STOCKADE DIARY November 13, 1943 - February 14, 1944 By Tatsuo Ryusei Inouye TULE WINDSONG Standing on the high desert of Tule Lake Only the wind blows Once my father's shakuhachi Now the memories of the survivors remain as they talk story Only the wind song will remain to tell the story - Tomiko Yabumoto Tomiko Yabumoto, born in 1941, just before the start of INTRODUCTION Of all the 10 War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps during World War II, Tule Lake is unique. In July of 1943, the United States government converted Tule Lake from a WRA camp into a segregation center to imprison people of Japanese descent that the government branded as "disloyal" to the U.S. To determine the alleged loyalty or disloyalty of a Japanese American, the U.S. government created a poorly-worded loyalty questionnaire. Respondents who gave unsatisfactory answers on this loyalty questionnaire were shipped to the Tule Lake Segregation Center until the Segregation Center became overcrowded and the government had to stop sending additional individuals. Subsequent research, however, have shown that there had been a variety of reasons that a Japanese American ended up at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Many of those reasons had little to do with issues of "loyalty" or "disloyalty" and had more to do with a desire to protest the government's discriminatory policies or to keep the family unit together or other related reasons. WHO WAS TATSUO INOUYE Tatsuo Inouye was born in Laguna, California, in 1910 to Suekichi and Taka Miyahara Inouye, the third of four children. At the age of three, he and his parents returned to their ancestral home in Kumamoto, Japan, where Inouye received his education. He would become a Kibei, an American of Japanese descent who was educated in Japan. He graduated from Uto Chugakko where he trained in judo, a martial art form literally translated as "the gentle way." Before he left Japan, he sought guidance from Mitsuru Toyama, a controversial right-wing political leader. He told Inouye to love the country of his birth as much as he loved Japan. At the age of eighteen, Inouye returned to the U.S. through San Francisco on the Shunyo Maru in 1928. There, he was reunited with his older brother, Tokio, who was living in Los Angeles. After a short stint working with his brother in a bicycle shop in Boyle Heights, then delivering ice, Inouye became a judo instructor for the children of thirteen pioneer Japanese American families, living in Antelope Valley, just north of Los Angeles. At the same time, he started taking English language courses at the Lancaster Junior College. As a member of the Kodokan Nanka Judo Yudanshakai, he was among those who demonstrated judo at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles. He held a fourth degree black belt during the war years. Among Inouye's language school students was Yuriko Lili Sugimoto, a mischievous and independent American-born Nisei, (second generation) who often was sent home from Japanese language school for acting up in class. She was the fifth of the seven Sugimoto children. She had a gregarious and outgoing personality in contrast to Inouye, who was stoic and introspective but despite or perhaps because of their personality differences, they found themselves attracted to each other and married in 1934. Shortly after they married, the couple did something almost unheard of at the time--they went on a six-month honeymoon to pay respects to the Inouye Family in Uto City, Kumamoto, then visited Toyama sensei. Pictures shows the couple traveled to Korea, then to China, where they took a picture walking on the Great Wall. At the outbreak of World War II, the couple had two children. When the U.S. government issued orders to imprison people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast into U.S. style concentration camps, the Inouye family was shipped to the Colorado River (Poston) WRA camp in Arizona, along with Yuriko's family, the Sugimotos from Lancaster, California. Before they left, the couple sold their store and a new refrigerator for $500 and rented out their home to a Mexican American family.

The Inouye Diary What follows are excerpts from a diary that Tatsuo Inouye kept while imprisoned in the stockade at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Inouye was arrested on November 13, 1943 and held in the stockade until February 14, 1944, for a total of three months and one day. The stockade — a prison within a prison — was created in November 1943, after martial law was declared and the army occupied the camp. The army invasion started on the evening of November 4, 1943, when a group of Japanese Americans tried to prevent Caucasians from driving trucks out of Tule Lake. The group suspected that the trucks were loaded with food that were meant to be served to the Japanese Americans but were, instead, being smuggled out and being sold on the black market. When the Project Director Raymond Best saw the crowd headed towards his residence, he overreacted and called in the army, which came in full force with tanks and jeeps mounted with machine guns. Initially, a hastily made tent stockade was created in an open field to imprison the Japanese American men captured on the evening of Nov. 4. Later, more men were rounded up, and barracks were constructed. The barrack stockades, which had been built to house about 100 men, swelled to 400 detained men over an eight-month period. The stockade had four guard towers, one standing at each corner, and was surrounded with barbed wire fencing. The barrack stockades were built far from the general camp population barracks, and there were several fences built between the barrack stockades and the general camp area, which prevented the stockade prisoners from communicating with the camp residents. Stockade inmates were not formally charged and were detained indefinitely. They were further denied visitation rights with family or friends. To protest the unfair and brutal treatment, stockade inmates held a number of hunger strikes. The stockade was finally destroyed after Ernest Besig of the Northern California American Civil Liberties Union and Wayne Collins, a San Francisco attorney, intervened. Today, no remnants of the wooden stockade barracks exists. The only structure that remains standing in that general area is a lone cement jail house, which visitors mistake for the stockade barracks. The following excerpts (PDF) from the Inouye diary begins with Tatsuo Inouye getting picked up by the military police in front of his children and being placed into the stockade. At this point, Tule Lake was already in turmoil for about a week. Several Tuleans had been picked up, beaten, and tossed into a make-shift stockade. ADDITIONAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND INFORMATION Citizen Isolation Center at Moab, Utah

Citizen Isolation Center at Moab, Utah

Block 42, Tule Lake WRA Center (1943)

Block 42, Tule Lake WRA Center

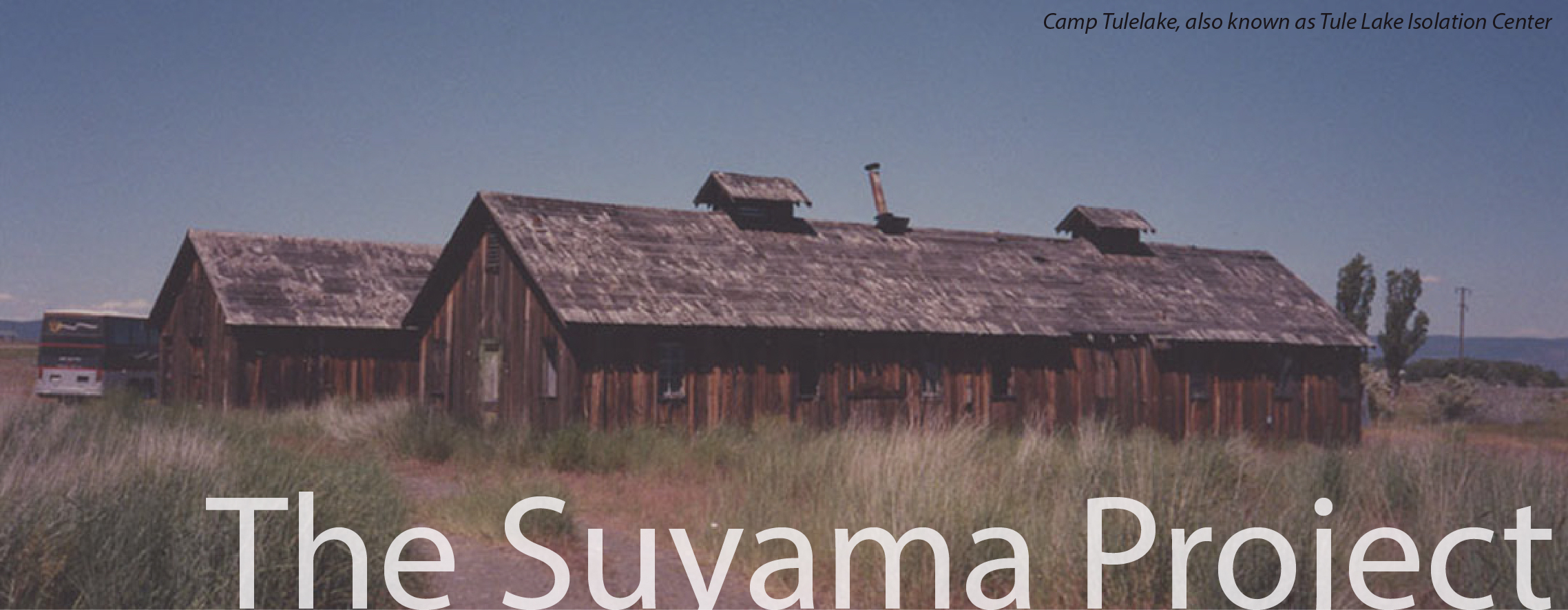

Camp Tule Lake

Camp Tule Lake

Mamoru Mori and James Tanimoto

Mamoru Mori and James Tanimoto

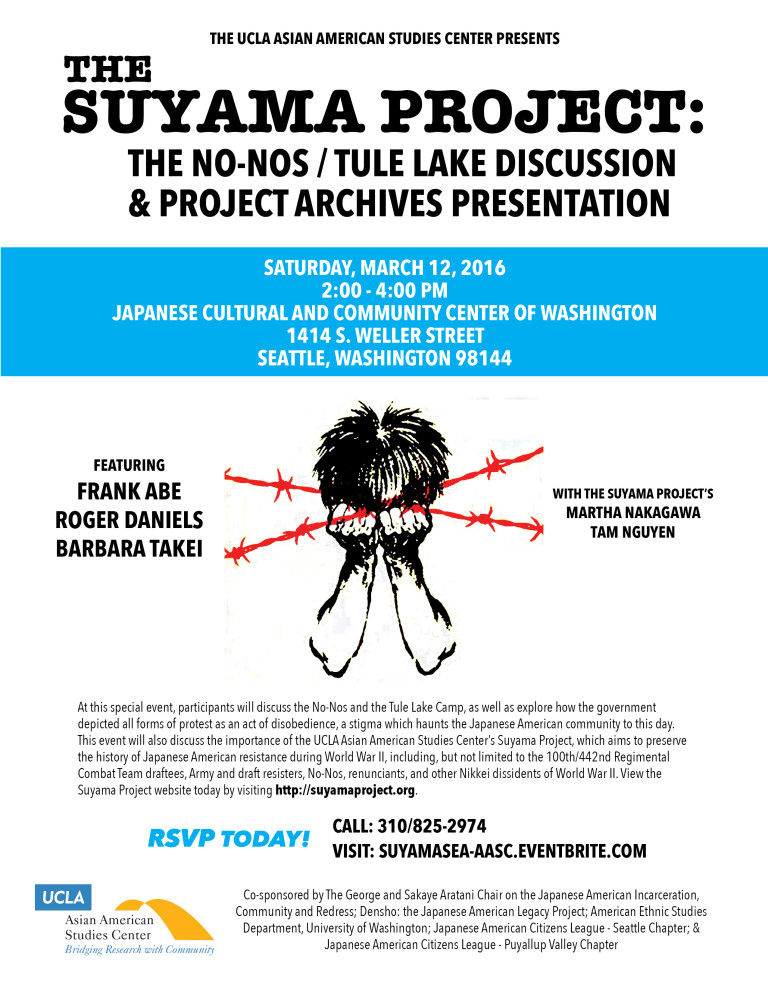

The No-Nos/Tule Lake Discussion, Seattle, WA

Notorious Tule Lake Segregation Center, Okada's 'No No Boy' Focus of March 12 Public Program in Seattle During wartime, how does a person prove their loyalty to their country? Is it restricted to military service? Or are there other forms of loyalty?

These and other questions of loyalty and patriotism will be discussed at a panel discussion on the World War II Tule Lake Segregation Center and the novel, "No No Boy" by John Okada.

Panelists will include Roger Daniels, University of Cincinnati professor of history emeritus and pioneer scholar in Japanese American history; Barbara Takei, an independent writer/researcher and board member of the Tule Lake Committee; and award-winning filmmaker and journalist Frank Abe.

Daniels and Takei are working on a history of America's worst concentration camp and will share some of their research findings.

Abe, who is compiling new research for a book on John Okada, will share his insights into how Okada took the story of the draft resisters and set it against the places where he grew up in postwar Seattle.

The program will take place on Saturday, March 12, from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington, 1414 South Weller Street in Seattle. A portion of the program will also be devoted to sharing about the UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Eji Suyama Endowment, which strives to preserve the history of Japanese American dissent during World War II.

On hand from UCLA will be David K. Yoo, PhD, Director of the Asian American Studies Center and professor in Asian American Studies.

The program is co-sponsored by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Endowment and the George and Sakaye Aratani Endowed Chair in Japanese American Incarceration, Redress and Community; Densho: the Japanese American Legacy Project; American Ethnic Studies Department, University of Washington; and the Japanese American Citizens League – Seattle Chapter and Puyallup Valley Chapter.

For more info, please contact the UCLA Asian American Studies Center at (310) 825-2974 or RSVP online at: suyamasea-aasc.eventbrite.com Block 42/Tule Lake Community Forum

Block 42/Tule Lake Community Forum Tule Lake War Relocation Authority Camp Block 42 Before Tule Lake was converted to a Segregation Center in 1943 for alleged “disloyal†Japanese Americans, Tule Lake was merely one of 10 War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps. However, the heavy-handed tactics of the Tule Lake WRA director caused tension between the administration and the inmates from early on.

Block 42/Tule Lake Community Forum In 1943, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) issued separate but similar loyalty questionnaires to the inmates that were poorly worded. The War Department's goal was to identify alleged "loyal" Japanese American men who were of draft age. The WRA's objective was to start releasing alleged "loyals" from the WRA camps. The War Department's form was given to Japanese American men and titled, "Statement of United States Citizens of Japanese Ancestry," DSS Form 304A. Answering this Selective Service form was voluntary. The WRA form was given to all adult Japanese Americans in the camps and titled, "Application for Leave Clearance," Form WRA-126, Rev. Answering this form was compulsory. The title of the two forms, the wording of the questions and the issue over whether the forms were voluntary or compulsory caused confusion among all 10 WRA camp inmates. At Tule Lake, relations between the administration and inmates deteriorated when the administration failed to provide basic information such as why the inmates were required to register for the so-called loyalty questionnaire. Tensions increased when the Tule Lake project director announced through the camp newspaper, the Tulean Dispatch, that anyone who interfered with the registration process would be fined up to $10,000 and/or imprisoned up to 20 years under the Espionage Act.

On or about Feb. 15, 1943, the men in Block 42 were ordered to register for the Selective Service. According to statements given by the men, a WRA representative visited Block 42 and told them if they chose to expatriate/repatriate to Japan, they would not have to register.

Several Block 42 men decided to apply for expatriation/repatriation. Many of these men had already applied for Selective Service and felt it unnecessary and even insulting to apply a second time. Some, who had registered before the war, had been given deferments for operating a farm, while others, who registered right after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, had been reclassified as enemy aliens.

On Feb. 19, a group of Block 42 men went to the Administration building and handed papers for expatriation/repatriation. A crowd started gathering around the Block 42 men but the incident ended without any problems.

The administration, however, took action against the Block 42 men on Feb. 21. Roughly 35 men from Block 42 were rounded up after dinner. One group was sent to the Klamath Falls jail and another, to the Alturas jail. Both groups were imprisoned for about seven days with no charges, no hearing or trial.

Meanwhile, the public arrest of the Block 42 men caused chaos in camp. Some in Tule Lake registered out of fear, while others became more defiant. The inmate-organized Planning Board and Community Council urged the Tule Lake administration to release the Block 42 men and proposed new registration procedures but the administration took a hard stance and refused to compromise. About a week after their arrest, the two group of Block 42 men were reunited at a former Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp named Camp Tulelake, located about 10 miles from the Tule Lake WRA camp.

One night, the Block 42 men were roused out of bed in the dead of night and ordered to stand outside the CCC barracks, according to brothers Mori and James Tanimoto, who were among the detained Block 42 men. Soldiers with rifles stood on both sides of a flood light focused on the men. The Tanimoto brothers thought they were facing a firing squad.

Although this incident ended with no injuries, the Tanimoto brothers speculated that the soldiers had intended to scare the men into answering the so-called loyalty questionnaire because shortly after this, on March 30, hearings were held. A Caucasian recreation hall served as the court room. The men were not given legal counsel, and alleged leaders were charged with one count of refusing to comply with the WRA's and not the War Department's order to register and one count of conspiring to impede the registration.

These alleged leaders were all shipped to the Moab Citizen Isolation Center where they were imprisoned for another four months.

The remaining Block 42 men were returned to Tule Lake about a month after their arrest. Unbeknownst to the Block 42 men and the other Tuleans, the administration had no legal authority to arrest the men. The War Department and the FBI had informed the Tule Lake administration that refusing to answer the loyalty questionnaire was not a violation of the Selective Service Act or the Espionage Act and did not carry a $10,000 fine and/or 20 years in jail. This information would not become public until decades later.

Ultimately, the Tule Lake administration's hardline approach towards the Tuleans contributed to the high number of inmates refusing to register.

According to "The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description" publication by the WRA, there were 77,842 inmates eligible to register for the questionnaire from all the 10 WRA camps. Of the 77,842 eligible, 3,254 did not register. Of the 3,254 who did not register, 3,218 were from Tule Lake.

As a result, the government chose to convert Tule Lake into a Segregation Center in the fall of 1943.

For more information: Collins, Donald. Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans During World War II. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps. New York: Morrow, 1976. Updated ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||