|

UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, Army and draft resisters, No-Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. The Suyama Project is made possible through the generous gift of an anonymous donor who wanted to honor and remember the legacy of resistance, broadly understood. |

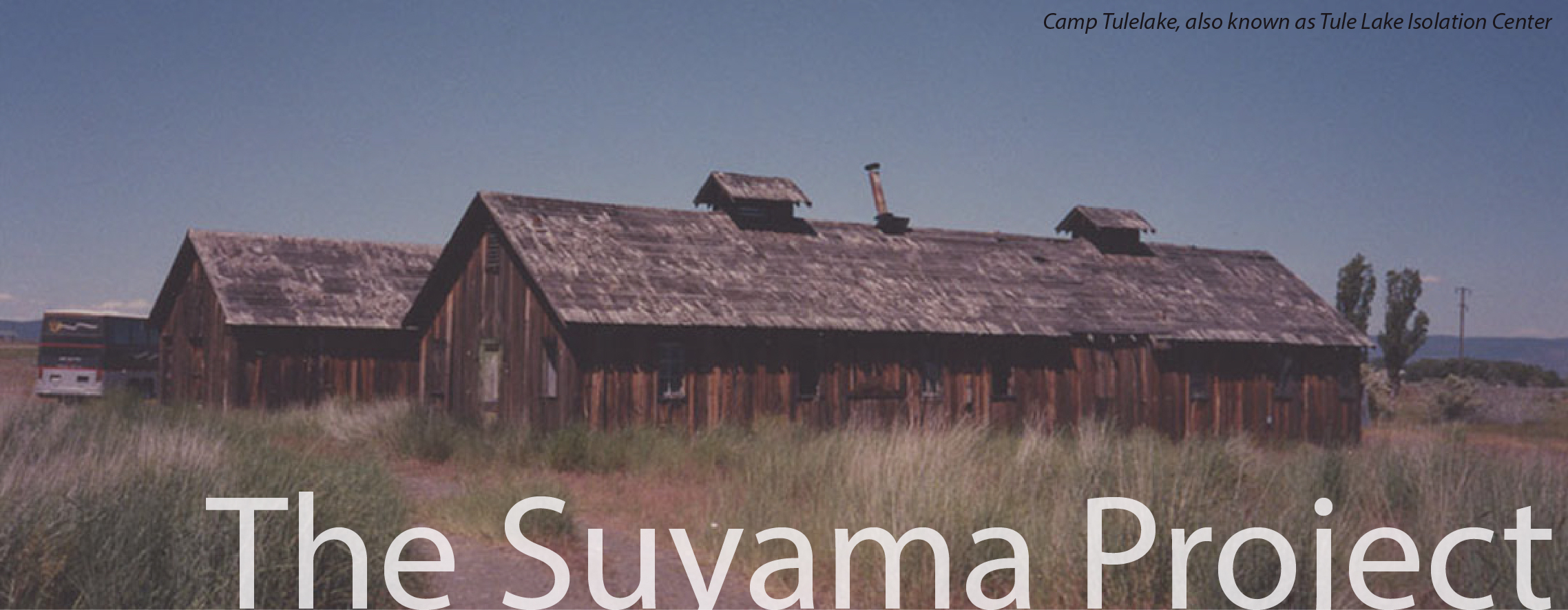

WORDS OF APPRECIATION FROM THE INOUYE FAMILY "My sisters and I thank our parents who gave us strength, perseverance, and principles that guided us throughout our lives. We had purpose (ikigai) and passion for our beliefs. Together, our parents surrounded us with love that we, in turn, shared with others. On a personal note, I wish to express my deepest thanks to UCLA Professor Alan Moriyama who inspired me to ask questions. I am honored that Professor Yuji Ichioka recognized the importance of the diary. We are blessed that Doshisha University Professor Masumi Izumi's skill and enthusiasm resurrected the project. Finally, I am filled with appreciation for my beloved husband, Kay, and sisters, Sayuri and Masako, and best friend, Sue Wong, for their support without which this project may have not been completed. The Inouye family must continue its legacy, which is to fight for civil rights in a just America. My heartfelt gratitude to Professor David Yoo, Martha Nakagawa, and Tam Nguyen, whose steady guidance made the diary accessible online through the Suyama Project." — Nancy Kyoko Oda UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, army and draft resisters, no-nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. A NOTE ON TRANSLATION ISSUES Inouye's diary is a rare, first person account of what occurred inside the Tule Lake stockade. As a prisoner in the stockade, he sent letters filled with love to his family. There were also letters of appreciation to friends and barrack neighbors, who had shown kindness to him and to his family. However, because his letters were checked by the military regularly, he kept the contents of his letters limited, but in one of his diary entries, Inouye wrote in Japanese: “I am writing this because I cannot battle with a rifle at this age. This diary is for my country, the United States of America.” Although he was imprisoned in the stockade without charge for an indefinite time, he never lost his sense of humor. His diary is peppered with bawdy jokes, sarcasm, and amusing observations. The original diary was written in Japanese, and the daunting task of translating the handwritten document was done by Professor Masumi Izumi from Doshisha University in Kyoto, Japan. It should be noted that Inouye received his education in Japan in the early 1900s, and similar to the way that the English language has evolved since Shakespeare's time, the kanji (Chinese characters) that Inouye used has changed over the decades. Another challenging aspect of translating Inouye's diary was that the Japanese language rarely uses direct pronouns such as "you," " I," "he" or "she," and additionally, Inouye often used quotations to indicate dialogue but did not specify the speaker. Part of this may be due to Inouye's attempt to cram as much as possible into limited paper space. It should also be pointed out that all letters exchanged between Inouye and his wife, Yuriko, while he was in the stockade were monitored and censored by the authorities. As a result, what is not said is just as important as what is actually written. Other times, he may write something that might mean something completely opposite. For example, he repeatedly writes how good the food is in the stockade so as not to worry his wife. Inouye also refers to the camp residents as "Japanese" but it is understood that he is referring to both the first generation immigrants (Issei), as well as American-born Japanese, and that when he refers to "Americans," he is referring to Caucasian Americans. After Inouye's release from Tule Lake at the end of World War II, his diary was carefully stored away in the basement until daughter, Kyoko, became interested in the U.S. concentration camps while attending classes at UCLA. In 1973, Kyoko embarked on a project to go through the camp diary with her father. During this process, Inouye added, deleted, and revised his original diary, resulting in several versions of the diary. The transcription task, however, remained unfinished until 2013 when a scholar capable of finishing the project was discovered by chance. Thus, a portion of the diary that includes Inouye's three months and one day imprisonment in the stockade is slated to be published in modern Japanese soon. The excerpts on the Suyama website is meant to introduce readers, through the account of one man's writings, to the constitutional and human rights violation perpetuated by the U.S. government and to, hopefully, inspire future generations to stay vigilant and to work towards preventing this from ever happening again. WAR YEARS — LOYALTY QUESTIONNAIRE In early 1943, the WRA and the War Department passed out a separate but similarly worded loyalty questionnaires. The purpose of the controversial questionnaire was to separate the alleged “loyal” Americans from the alleged “disloyals” in an effort to accelerate the movement of Japanese Americans out of the WRA camps and at the same time, to determine the willingness of draft-age Japanese American men to serve in the military. Questions 27 and 28 became the most problematic, and they were later revised on the WRA form.The early army form read: Question 27 — “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” Question 28 — “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and foreswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?” Issues arose whether answering “yes” to question 27 meant a Japanese American was volunteering for the army. Many found question 28 the most insulting since a “yes†answer implied that the respondent had once sworn allegiance to the Japanese Emperor. On the early WRA forms handed out to Issei (immigrant) males, question 27 asked whether the respondent “will be willing to volunteer for the Army Nurse Corp or the WAAC (Women's Army Auxiliary Corp).” Question 28 also placed the Issei in a no-win situation. Since the Issei, were, by law, ineligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens, they would become stateless if they answered “yes” but faced the possibility of deportation if they answered “no.” Inouye answered “no” to question 27 and “neutral” to question 28. However, he changed his answers to “yes,” after he considered the possible objections of his in-laws. Inouye's initial response had nothing to do with “disloyalty.” Rather, since his parents and a brother lived in Japan, he did not want to find himself caught in a situation where he would have to fight his own family should he be drafted into the U.S. military and sent to fight in the Pacific. The U.S. government, however, did not take such sensitivities into consideration and deemed any answer other than a “yes” to be a sign of “disloyalty” and transferred these respondents and their family to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. TULE LAKE SEGREGATION CENTER When Tule Lake was designated as a segregation center in mid-1943, it became a maximum-security prison with a new eight-foot wire mesh fencing, which was topped off with barbed wires sloping inwards. In addition, several new guard towers were built and a full battalion of military police with armored cars and tanks were called in. On Oct. 7, 1943, Inouye, wife, Yuriko Lili and their two children left the Poston (Colorado River) WRA camp in Arizona, and arrived at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California, on Oct. 9, 1943. Upon Inouye’s transfer to Tule Lake, he immediately set about to open a judo practice in one of the empty barracks. His friend, Iwao Shimizu, perhaps captured Inouye's sentiment when, after the war, he wrote a letter to Inouye, saying in Japanese, “The construction of the dojo in Tule Lake Camp is based on the teacher’s zeal and sincerity. While one year is not long in the face of the universe's long history, it is a precious year when our life is no longer than fifty years.” Inouye was on a mission to build the men up, morally and physically, since their lives had been disrupted by the war. This attracted the attention of camp administrators, who kept an eye on him as a possible threat to camp authority The Inouye family was among the approximately 9,000 inmates from other WRA camps that had not answered the controversial loyalty questionnaire to the government’s satisfaction and were shipped to the Tule Lake Segregation Center between September and October of 1943. With the sudden influx of people, Tule Lake became overcrowded. To address the food shortages and unsanitary living conditions, the new arrivals organized a committee to negotiate with Tule Lake Project Director Raymond Best. Best, however, was a former Marine Corp veteran of World War I and former director of the Moab and Leupp Citizen Isolation Centers. He had a top down management style and was not open to negotiating with the Tuleans. Protest erupted after Best mishandled a Tule Lake farm accident in October 1943 that resulted in one fatality and 29 injured, with some seriously wounded. Best refused to allow a mass public funeral for the deceased and compensated the widow with only two-thirds of the $16-a-month salary of the deceased farm worker. In response, angry Tuleans initiated a work stoppage that evolved into a strike, demanding improved working conditions, reasonable compensation to the injured, and better safety measures to prevent future accidents. Best countered by firing the Tuleans and bringing in strikebreakers from the Poston (Colorado River) and Topaz (Central Utah) WRA camps. To add insult to injury, the strikebreakers were paid higher wages than the Tuleans. On Nov. 1, 1943, National WRA Director Dillon Myer visited Tule Lake. The Daihyosha-kai, the Negotiating Committee, presented Myer and Best with a set of grievances. Outside the meeting, more than 5,000 Tuleans peacefully assembled in support of the Negotiating Committee, but Best refused to address the issues. On the evening of Nov. 4, 1943, a group of Tuleans attempted to stop a number of trucks from leaving the camp site since they suspected the trucks were filled with food that were designated for the Tuleans. A number of Tuleans were arrested that evening and beaten savagely. They were later tossed into a make-shift jail in the stockade area. In the days following this incident, martial law was declared and a curfew strictly enforced. The military police also went from barrack to barrack to conduct a search for Daihyosha-kai members. The stockade swelled to 200 men. Among them would be Inouye. EXPATRIATION/REPATRIATION On July 20, 1943, Inouye made an initial request for "repatriation" to Japan through the Spanish Consulate, which was the neutral negotiating country between the U.S. and Japan. Although Inouye, as a U.S. citizen, should technically be requesting “expatriation” to Japan rather than “repatriation,” Japanese law allowed Japanese Americans born in the U.S. before 1924 to be given automatic Japanese citizenship, allowing them dual citizenship. Inouye made a second, formal request on April 22, 1944 for repatriation for himself and his wife and expatriation for his two American-born daughters. Inouye never renounced his U.S. citizenship, and after his oldest daughter, Sayuri, fell very ill with rheumatic fever, the Inouye family was given permission in November 1945 to leave the Tule Lake Segregation Center and return to Los Angeles to obtain medical care for their daughter. Just before leaving Tule Lake, a third daughter, Kyoko, was born. The Inouye and Sugimoto family reunited at Lancaster. From there, Inouye moved, by himself, to East Los Angeles where the Gomez family had been faithfully paying property tax during the war on a home owned by the Inouye family. Since housing was in short supply after the war, the Gomez family continued to live in the Inouye family home, while Inouye settled down in the basement. Shortly thereafter, the remaining Inouye family and Yuriko’s two sisters joined Inouye and the Gomez family. The group of twelve people lived under one roof for several months. Inouye was offered a job as a grave digger at the local cemetery, but like many other Japanese American men at that time, he decided to become an independent gardener and had clients in the Monterey Park and the San Gabriel Valley area. Inouye also restarted his judo practice in the family garage. A few years later, classes were moved to a larger facility at the Konko Kyo Church in East Los Angeles and then, to a four-car garage space of a newly-built duplex complex in East LA where the family had moved into. Inouye’s three daughters also practiced judo, earning brown and black belts from the Nanka Yudanshakai. Judo principles of mutual welfare and benefit were always core Inouye family values. Yuriko Lili took care of the three growing children and supplemented the family income by working at a warehouse, packing cheese and later, as a floral designer. At home, she was always busy, sewing clothes for the three daughters or making tablecloths or other items for the house. According to the Inouye daughters, their mother’s quiet strength had sustained their father in camp and had kept the family together, especially when the father was hauled off to the stockade. While their mother kept her feelings to herself, the daughters recalled seeing their mother break out crying at times while reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in camp, one outward sign of the emotional turmoil and frustration that Yuriko Lili held inside. The daughters noted that after the war, Yuriko Lili did not want to talk about the camps for fear that she would be picked up by the authorities, but her voice comes alive in the many camp letters that the family had saved. As a sign of their parents’ love for each other, the daughters recalled how one year, their father bought the biggest heart-shaped box from See’s Candies that he could afford and presented it to their mother on Valentine’s Day. Once the heart-shaped box became empty, the father wrapped it in plastic and saved it in the basement. Thereafter, whenever Valentine’s Day rolled around, the father would refill the box with candy and present it to his wife. He did this for several years, according to the daughters. Valentine’s Day had special meaning to the couple since this was also the date that Inouye had been released from the stockade in 1944. In 1990, Inouye took his wife for a final trip to Japan to visit his family home in Uto city and to spend time with his high school friends. The daughters noted that he was still protective of his wife, although he himself was already 87 years old. The three daughters grew up in Los Angeles, listening to their father’s recollections of the camp years. When Kyoko started attending UCLA during the 1970s, she urged her father to share his diary. She started transcribing the diary as a UCLA class assignment, and the professor, Alan Moriyama, even invited Kyoko’s father to speak to the class about the diary. In 1994, the eldest daughter, Sayuri, accompanied her father to the Tule Lake Pilgrimage, so he could have one last look at the former camp site. In 2009, the middle daughter, Masako, an artist, attended the Tule Lake Pilgrimage for the first time since her imprisonment and found healing from her childhood trauma of incarceration. She would go on to create several ceramic sculptures with names such as “Gaman” (to persevere) and “Show Me the Way Home.” During the 2000s, Kyoko would become active in preserving the stories of Japanese, German, and Italian alien immigrants, and Japanese taken from Peru who were held in the Tuna Canyon Detention Station in Tujunga, California. It was one of several detention centers where Issei leaders had been imprisoned without charge shortly after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Kyoko would not return to her father's diary project until 2013 when she and sister Masako attended a Japanese American National Museum conference and met Professor Masumi Izumi from Doshisha University in Kyoto. Izumi agreed to translate the diary. Although Inouye had burned some of his diary pages and had written some thoughts cryptically, whose true meaning lie hidden behind irony, Inouye clearly wanted his story told. The following is what he wished to share with the public. JAPANESE HONORIFICS Since Japan is a stratified society, the use of honorifics indicates the relationship and status of one person to another. This translation version did not keep all honorifics intact but Inouye does refer to the use of honorifics in his diary. The following is a simple guide to some of the honorifics appearing in the diary: — san: This is the most common and all-purpose honorific that can mean Mr., Mrs., Ms., Miss, etc. — kun: This suffix is attached to the end of a male name to denote a boy or a male, who is younger or of a younger status — shi: This suffix is another polite way to say Mr. or refer to a family clan. DISCLAIMER/COPYRIGHTS Copyright © 2018. All rights reserved. UCLA Asian American Studies Center, Nancy Kyoko Oda. No reproduction or representation of any of the content on this website, including text, images, and files downloadable from this website, without the written permission of the copyright owner(s). For questions or inquiries on content use, please contact us. |