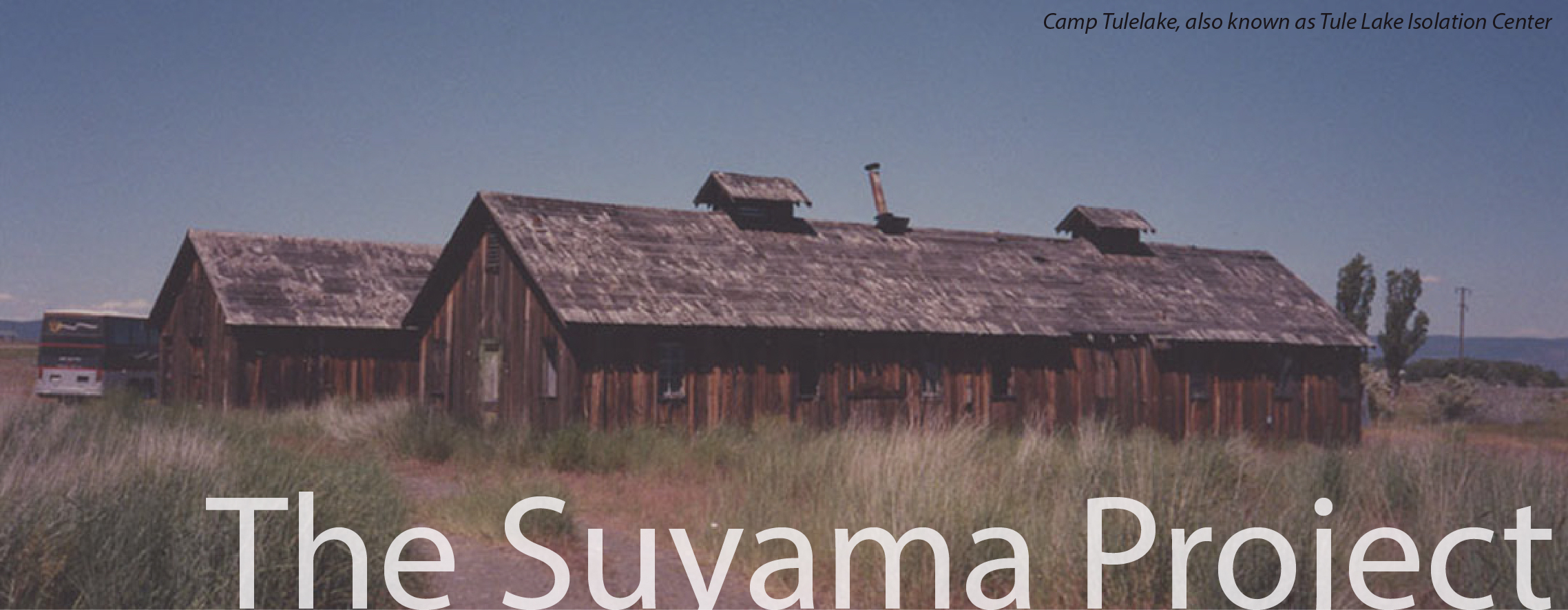

|

UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, Army and draft resisters, No-Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. The Suyama Project is made possible through the generous gift of an anonymous donor who wanted to honor and remember the legacy of resistance, broadly understood. |

Category Archives: Riots/Unrest The No-Nos/Tule Lake Discussion, Seattle, WA

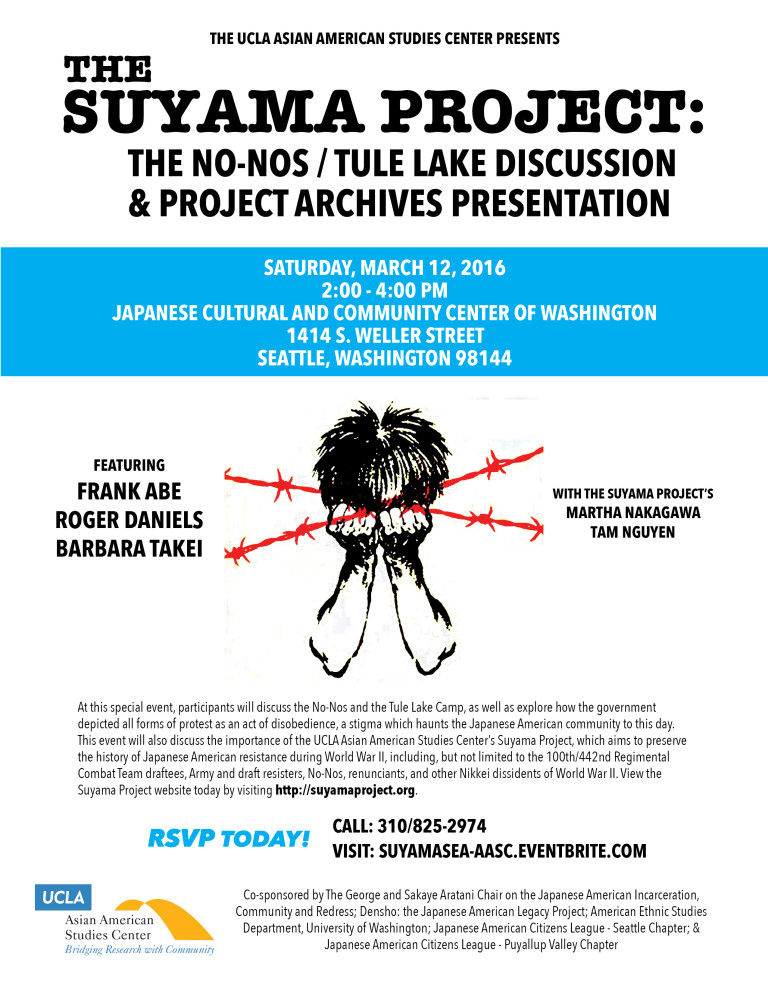

Notorious Tule Lake Segregation Center, Okada's 'No No Boy' Focus of March 12 Public Program in Seattle During wartime, how does a person prove their loyalty to their country? Is it restricted to military service? Or are there other forms of loyalty?

These and other questions of loyalty and patriotism will be discussed at a panel discussion on the World War II Tule Lake Segregation Center and the novel, "No No Boy" by John Okada.

Panelists will include Roger Daniels, University of Cincinnati professor of history emeritus and pioneer scholar in Japanese American history; Barbara Takei, an independent writer/researcher and board member of the Tule Lake Committee; and award-winning filmmaker and journalist Frank Abe.

Daniels and Takei are working on a history of America's worst concentration camp and will share some of their research findings.

Abe, who is compiling new research for a book on John Okada, will share his insights into how Okada took the story of the draft resisters and set it against the places where he grew up in postwar Seattle.

The program will take place on Saturday, March 12, from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington, 1414 South Weller Street in Seattle.

A portion of the program will also be devoted to sharing about the UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Eji Suyama Endowment, which strives to preserve the history of Japanese American dissent during World War II.

On hand from UCLA will be David K. Yoo, PhD, Director of the Asian American Studies Center and professor in Asian American Studies.

The program is co-sponsored by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Endowment and the George and Sakaye Aratani Endowed Chair in Japanese American Incarceration, Redress and Community; Densho: the Japanese American Legacy Project; American Ethnic Studies Department, University of Washington; and the Japanese American Citizens League – Seattle Chapter and Puyallup Valley Chapter.

For more info, please contact the UCLA Asian American Studies Center at (310) 825-2974 or RSVP online at: suyamasea-aasc.eventbrite.com Poston Strike Community Forum

Poston Strike Community Forum Riots / Unrest

From the spring until the fall of 1942, the Japanese American community was in constant flux as the Army sent some groups directly to camps, while with others, the Army temporarily imprisoned them at assembly centers and then shipped them off to camps.

Because Japanese Americans were tossed into hastily made living quarters, they endured overcrowding, lack of adequate food and shoddy medical care, among other issues. But Japanese Americans did not quietly endure or "gaman" under these tense living conditions. They organized and voiced their complaints from early on.

SANTA ANITA ASSEMBLY CENTERAt the Santa Anita Assembly Center, there were two major protests. The first occurred in June 1942, when Japanese Americans, employed in the camouflage net operation, initiated a sit-down strike.

The administration had been using pressure tactics on the Japanese Americans in order to meet net quotas, and thus, were forcing them to labor under the hot sun, often in a kneeling position for eight-hours. Many of the workers were also allergic to the hemp nets, burlap, and dyes used in the operation. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that once the workers finished their shifts, they had to stand in long mess hall lines for their meals.

The strike, however, was quickly resolved after inmate representatives met with administrators later that day and were able to negotiate better working conditions and food provisions.

The second, more violent, incident occurred on August 4, 1942, when the internal police engaged in a routine search for contraband. As items were confiscated from the inmates, a crowd started to gather, and a suspected informant was beaten by the other inmates.

About 200 military police were dispatched to quell the unrest, and martial law was declared. No meals were served that night, and a number of inmates were rounded up and held in the bathroom of the grandstand, which was converted into a makeshift jail. The military police withdrew on August 7.

WCCA/WRA CAMPSThe three earliest camps to open were Manzanar, Tule Lake and Poston (Colorado River), and all three camps experienced unrest from their inception.

From the beginning, leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) became targets of intimidation and assault due to the organization's public stand of encouraging cooperation with the government in the imprisonment process.

Within the Japanese American community, it was widely suspected that JACL members had turned over names of Issei community leaders to the FBI, which had allowed the FBI to round up and incarcerate Issei leaders shortly after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. In turn, the leadership vacuum that followed allowed the government to install the Nisei, mostly JACLers, into positions of leadership.

The feeling of JACL betrayal intensified within the Japanese American community when the JACL began advocating the re-opening of the armed services for Japanese Americans.

At all three camps, unknown assailants, who were never caught, attacked JACL leaders or anyone suspected of being too friendly with War Relocation Authority (WRA) administrators. They were often referred to as "informers" or "inu" (dog).

Much of JACL's wartime collaboration with the government has been documented in the Deborah Lim Report [www.Densho.org or www.resisters.com] and can also be found in declassified FBI reports.

In addition to the JACL issue, all three camps experienced other forms of public disturbances.

Poston (Colorado River)

Manzanar

Tule Lake

Loyalty Questionnaire RegistrationIn early 1943, the War Department and the WRA conducted a joint registration process in which they had camp inmates fill out a so-called loyalty questionnaire.

At Minidoka, several meetings were held to discuss the loyalty questionnaire, and by the time registration started at Minidoka, the inmates were aware of the loyalty questionnaire's purpose. For this reason, registration went the smoothest at Minidoka.

At Heart Mountain, the Citizens' Congress, which formed in response to the loyalty questionnaire, advocated compliance with registration only after the government met certain conditions. The group sent out telegrams to the other nine camps, requesting their cooperation in the conditional registration, including the demand for the restoration of their citizenship rights. However, the Heart Mountain group received no unified response from the other camps, and thus, this movement gained no traction.

At Topaz (Central Utah), the Issei formed a Committee of Nine, which informed the project director that the Issei could not properly answer question 28. The project director contacted WRA headquarters in Washington DC, but before there was a response, the Committee of Nine sent a stronger petition, stating that the Issei resolved not to answer question 28. To appease the Issei, WRA director Dillon Myer's staff drafted alternative wordings for question 28 on forms passed out to the Issei.

Encouraged by the Issei's success, the Kibei and Nisei at Topaz organized around the registration issue. The Nisei formed a Committee of Thirty-Three but resistance against registration was thwarted when the WRA sent Dr. John Embree, director of WRA's Community Analysis Section, who was able to stir up patriotism coupled with threats of criminal prosecution.

Along with registration process, the issue of the draft came to the forefront. Although Heart Mountain had the only organized draft resistance movement, seven other WRA camps also had Nisei men of draft age protest conscription from the camps without the restoration of their civil rights.

Regarding the loyalty questionnaire registration at Tule Lake, Tuleans were given no opportunity to participate in open discussions regarding the process. The administration organized one meeting, which was held on the eve before registration was to open, and no question and answer session was allowed at this meeting. This led to many Tuleans refusing to register.

When the Tule Lake administration could not persuade the inmates to register voluntarily, the administration announced through the camp newspaper that answering the loyalty questionnaire was compulsory.

To ensure compliance, the administration made an example of Block 42, which had a high number of men refusing to register. The Block 42 men were rounded up and taken out of Tule Lake for about a month.

Since Tule Lake had the highest number of inmates who either refused to register or answered "no" to questions 27 and/or 28, the WRA converted Tule Lake into a Segregation Center and began shipping inmates from the other nine WRA camps who fell under the WRA's definition of a "no no."

Another 6,000 original Tuleans, who did not fall under the WRA's "no no" category but who did not wish to move again, remained at Tule Lake.

When the government started shipping in thousands of so-called “no no†inmates from the other camps into Tule Lake, the camp became a powder keg since it was unprepared to house the new arrivals. Overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions caused tension between the original Tuleans and the new arrivals and between the inmates and the Tule Lake administrators who were not sympathetic to the inmates' needs such as dust control, improvement of food, better block facilities.

In late October 1943, a Tulean was killed in a truck accident. The truck had been driven by an inexperienced minor and had overturned, killing one Tulean from Topaz and seriously injuring five of the twenty-eight riders. A farm work stoppage was called.

Tule Lake Project Director Raymond Best mishandled the situation by refusing to allow a public funeral and further angered the inmates by cutting off the public address system when the inmates disregarded Best's orders and organized a public service where thousands turned out.

To counter the work stoppage, Best brought in inmates from the other WRA camps to harvest the crops.

Relations between the administrators and Tuleans continued to deteriorate, and when WRA Director Dillon Myer visited Tule Lake, a crowd of 5,000 inmates gathered to voice their dissatisfaction and presented a list with 18 demands.

Three nights later on November 4, 1943, a group of inmates attempted to stop a truck driven by Caucasians. The inmates suspected these trucks were carrying stolen food meant for the inmates out of camp to be sold on the black market. A scuffle ensued, and Best called in the Army, which rolled in with tanks and jeeps equipped with machine guns.

Several Tuleans, who were hauled off by internal security officers that night were beaten severely. Two WRA female workers later gave statements to ACLU lawyer Ernest Besig that they found a broken baseball bat, blood splatter and chunks of black hair in the Administration Building, which they had to clean up.

Martial law was declared; curfew was imposed; and schools were shut down. Army men participated in unannounced late night search and seizure tactics of inmate barracks, and any group that failed to disperse immediately were hit with tear gas.

Further, any Tulean suspected of being leaders or connected with the leaders were hauled off and imprisoned in a newly-built stockade, a prison within the concentration camp. Those detained in the stockade participated in three hunger strikes.

In desperation, the inmates contacted the Spanish Consul, which acted as the neutral party between the U.S. and Japanese governments. Although the Spanish Consul General visited Tule Lake on December 13, 1943, the Consul General voiced doubt that he could intervene on matters between the U.S. government and U.S. citizens of Japanese descent.

On July 1, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Public Law 405, which allowed U.S. citizens to renounce their citizenship in time of war, upon the approval of the attorney general. Although this law affected all U.S. citizens, this bill was passed with the intention of legally deporting American-born Tuleans to Japan by having them renounce their U.S. citizenship.

By the fall of 1944, Tule Lake had broken up into different factions with some advocating continued protest against the government, while others wanted a more conciliatory approach. Physical violence became common.

By 1945, the re-segregation group came to prominence and advocated segregation within Tule Lake to separate those who wanted to remain in the U.S. with those who wanted to go to Japan.

To crack down on the rise of the re-segregationists, the WRA started rounding up members and shipping them off to the Santa Fe Department of Justice camp.

As the war started to wind down, those who renounced their U.S. citizenship under these extreme conditions came to regret their actions.

Attorney Wayne Collins would file legal suits on behalf of close to 6,000 renunciants in an effort to restore their U.S. citizenships. The last renunciation case would not come to a close until March 6, 1968. |