|

UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, Army and draft resisters, No-Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. The Suyama Project is made possible through the generous gift of an anonymous donor who wanted to honor and remember the legacy of resistance, broadly understood. |

Category Archives: Renunciants Mori Tanimoto and Hiroshi Kashiwagi

Mori Tanimoto and Hiroshi Kashiwagi

Renunciants During World War II, several bills were introduced in Congress with the goal of stripping United States citizenship from people of Japanese descent. One politician went so far as to propose invalidating the U.S. citizenship of all Japanese Americans who had answered "no" to questions 27 and 28 on the so-called loyalty questionnaire.

Anti-Japanese elected officials, coupled with pressure from anti-Japanese organizations such as the Native Sons of the Golden West, resulted in the passage of Public Law 405 on July 1, 1944. This bill allowed a U.S. citizen to renounce their citizenship in time of war, upon the approval of the attorney general.

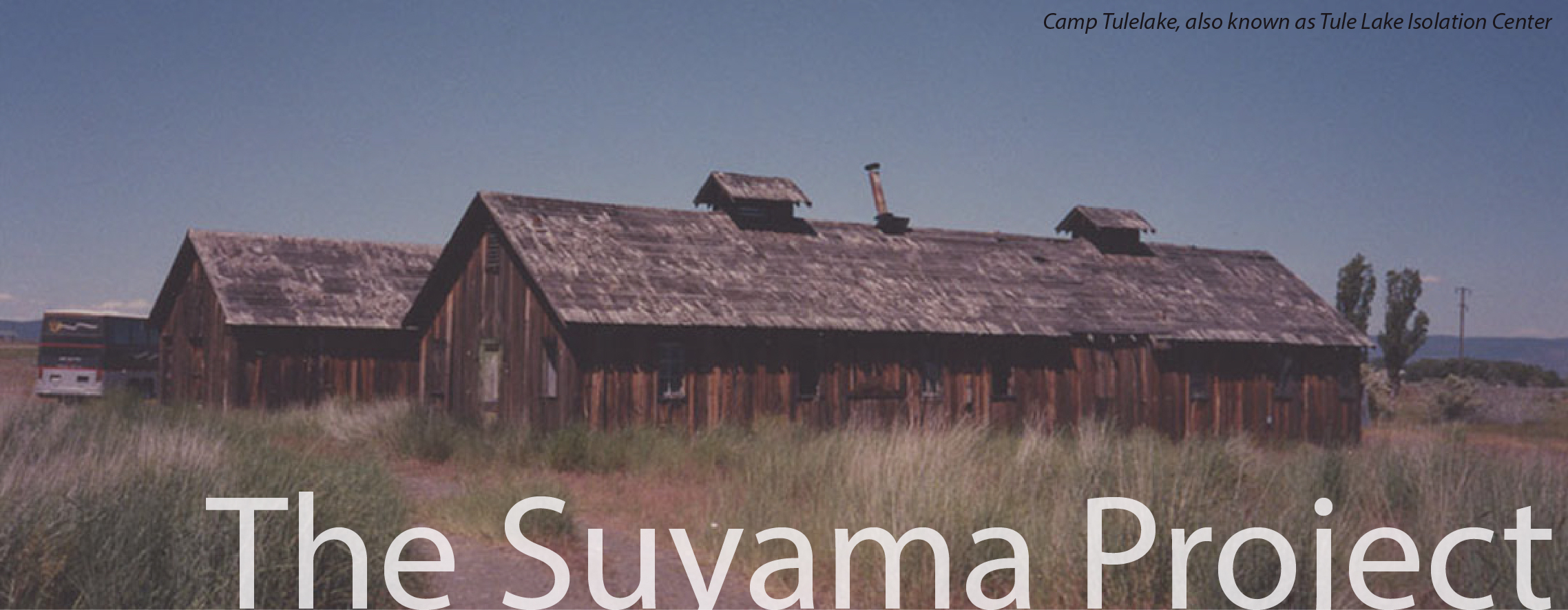

Although this bill affected all U.S. citizens, it was passed with the intention of handling what government officials deemed "disloyals" at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. The U.S. government could not legally deport people of Japanese descent as long as they held U.S. citizenship, but once a U.S. citizen renounced their citizenship under Public Law 405, the government could declare them as "enemy aliens," subject to internment at a Department of Justice (DOJ) camp and deportation.

A total of 5,589 citizens from the nine War Relocation Authority camps and the Tule Lake Segregation Center renounced; of that, 5,461 came from Tule Lake.

It has since been documented that renunciation had little to do with "disloyalty." The hard stance of the Tule Lake administration and the abusive treatment of those imprisoned in the Tule Lake stockade contributed to fear and confusion among the Tuleans.

As a result, some renounced out of anger, while others were misled to believe that renouncing would keep the family unit together. Another misconception that took root among the Tuleans was the thought that renouncing would allow them to wait out the war in Tule Lake and upon the end of the war, allow them to return to their West Coast homes.

Still others, who renounced, demanded segregation within Tule Lake to separate those who wanted to remain in the U.S. from those who were fed up by their unconstitutional treatment and wished to go to Japan.

When a DOJ team began holding hearings in January 1945, for those who had applied for renunciation, many Tuleans began having second thoughts and sought to reverse their renunciation.

The DOJ, however, was not amenable to allowing renunciants to resettle in the U.S. and sought to deport them. In response, Tetsujiro "Tex" Nakamura, a Tulean who had not renounced, began organizing the renunciants.

Nakamura enlisted the support of San Francisco attorney Wayne M. Collins and spearheaded the Tule Lake Legal Defense Committee.

On Nov. 13, 1945, Collins filed a mass petition to stop the immediate deportation of Tuleans two days before the ship was to depart for Japan. Collins also argued to have the U.S. citizenship of the renunciants restored, and at the same time, filed separate papers for minors whose parents had renounced the U.S. citizenship of their children.

Collins' main defense in the lawsuit was government duress, starting with the mass removal of Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast to imprisonment in the camps.

The lawsuit was dealt a blow when the Murakami vs. U.S. case was settled. The Murakami case had preceded Collins' case and had been filed by the Southern California ACLU. The case restored citizenship to three individuals and placed the blame of renunciation on the individual, rather than on government duress.

As a result, Collins would be forced to file individual appeals to restore citizenship rather than en masse. The final case would not be concluded until March 6, 1968, 23 years after Collins had filed the initial lawsuit.

Of the 5,589 applications of renunciation accepted by the U.S. government, 5,409 Japanese Americans petitioned to have their citizenship restored, and of that, 4,978 had their U.S. citizenships restored. |

|||||||||||||||||||||