|

UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, Army and draft resisters, No-Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. The Suyama Project is made possible through the generous gift of an anonymous donor who wanted to honor and remember the legacy of resistance, broadly understood. |

| Draft Resisters An estimated 315 Japanese American men from the continental United States and Hawaii refused to serve in the U.S. military during World War II, but draft resistance, in reference to Japanese Americans, has generally come to mean those who refused to serve while incarcerated in U.S. concentration camps during World War II.

Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese American men were volunteering or being drafted into the U.S. Army similar to any other American.

Six months after Pearl Harbor, the War Department and the Selective Service stopped inducting Japanese Americans and categorized them as IV-C, aliens not eligible for service.

In July 1942, the Army formed a committee to discuss the future of about 5,000 Japanese American soldiers inducted into the Army before or immediately after Pearl Harbor.

In Hawaii, Japanese American soldiers already in the Army were assigned to the 298th and 299th Infantry Regiment, which later became the famed 100th Battalion. The soldiers of the 100th made a name for themselves as fierce fighters after seeing heavy action in Italy.

In contrast to the treatment of Japanese Americans in Hawaii, people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast were being uprooted from their homes and placed into U.S. concentration camps. Many had never heard of Pearl Harbor before Japan's attack.

Propaganda from Japan pointed to the U.S. camps as yet another discriminatory policy against the Japanese living in the U.S.

To counter such negative publicity, the War Department decided to form an all-Japanese American unit, which would be known as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Announcements for volunteers for the 442nd went out in early 1943. Close to 10,000 Japanese Americans from Hawaii volunteered, with about 2,600 being accepted for induction, while a paltry 1,256 Japanese Americans out of more than 23,000 draft-age men answered the call for volunteers from the camps. Of that, about 800 were inducted.

When the quota for Japanese American volunteers from the mainland fell far short of expectation, the government resorted to reinstating the draft for Japanese Americans. Those who refused to serve were threatened with huge fines (about $10,000) and prison time (about 30 years).

While there were different reasons why Japanese American men from the mainland resisted the draft, this gave them yet another way to protest their imprisonment from within the 10 War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps. The government arrested these draft resisters and put them on trial.

The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) actively opposed the draft resisters, and JACL leaders were given access to several draft resisters awaiting trial in jail in an effort to change their minds and possibly gather information for the government.

At the Heart Mountain WRA camp, the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee (FPC) became the only organized movement from within the 10 WRA camps to oppose the drafting of Japanese American men without the restoration of their rights as US citizens. The Heart Mountain Sentinel, a pro-JACL camp newspaper, publicly condemned the draft resisters as "yellow bellied cowards."

James Omura, the editor of the Rocky Shimpo, a newspaper that was based in Denver where Japanese Americans were not incarcerated, supported the FPC. Omura was the only newspaper editor to publish the FPC news releases, and he also wrote editorials in support of the FPC's demand that US citizenship rights be restored before induction into the Army.

Omura's editorials increased subscribers from the 10 WRA camps but also caught the attention of the government, which forced Omura to resign from the Rocky Shimpo. He was, then, arrested and put on trial with seven FPC leaders in Cheyenne, Wyoming, on charges of counseling, and aiding and abetting others to violate the draft. The FPC leaders were found guilty and sentenced to federal prison, but Omura was acquitted on First Amendment grounds of freedom of the press.

On average, the draft resisters from the different WRA camps received prison sentences of three years, but the lack of a uniform U.S. court system policy gave rise to a range of punishments that went from prison terms to fines. At the Poston (Colorado River) WRA camp, draft resisters were fined a penny per person with no prison time, except for a select few who were sentenced to jail.

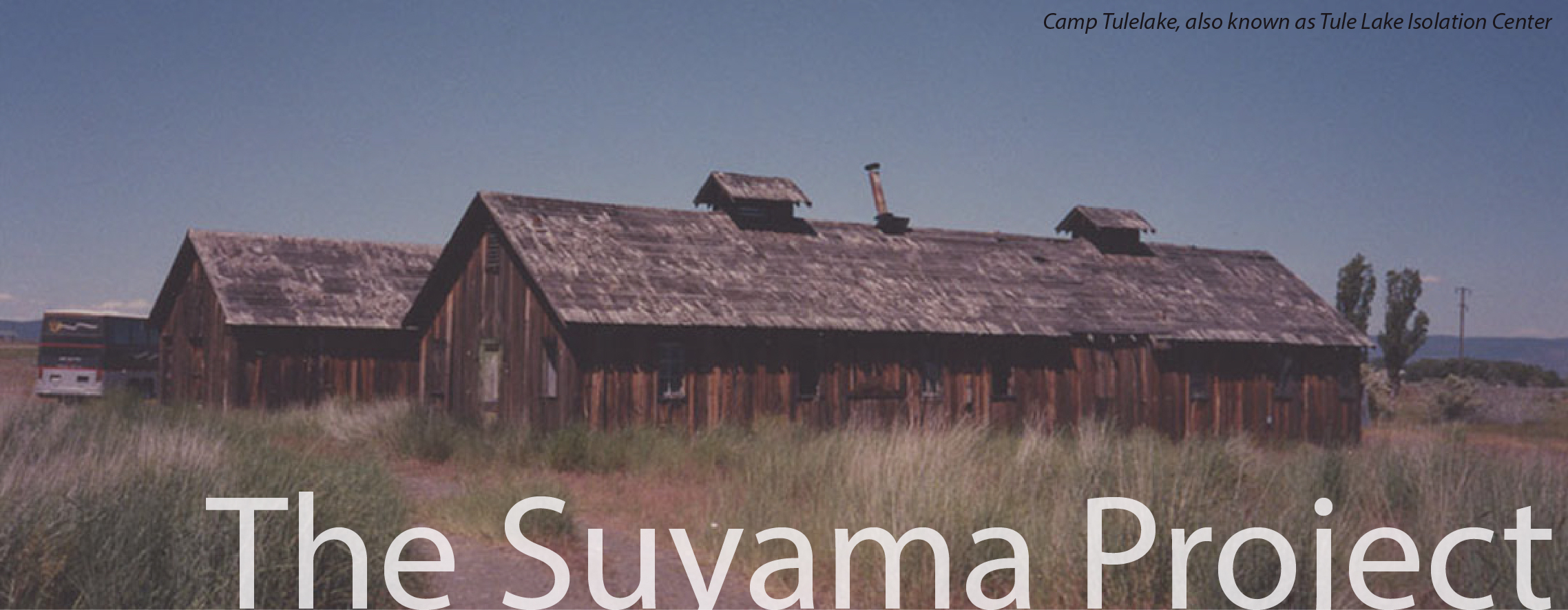

Only Judge Louis E. Goodman, who presided over the 27 Tule Lake draft resisters, dropped the charges entirely for the Tule Lake draft resisters.

Meanwhile, the Heart Mountain FPC leaders, while incarcerated at the Leavenworth federal penitentiary, went on to win their case on appeal.

On Dec. 23, 1947, President Harry Truman issued a presidential pardon to those who had violated the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. On the list were 284 Japanese American names but surviving resisters have confirmed that several names of known draft resisters were omitted from the list. |