|

UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Project aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including, but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, Army and draft resisters, No-Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents of World War II. The Suyama Project is made possible through the generous gift of an anonymous donor who wanted to honor and remember the legacy of resistance, broadly understood. |

Category Archives: No-Nos Jimmie Omura's 'Return to the Wars' Diary An edited and annotated version of James Omura's diary is now available at suyamaproject.org, a website sponsored by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, which aims to preserve the history of Japanese American resistance during World War II, including but not limited to the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team draftees, draft resisters, No Nos, renunciants, and other Nikkei dissidents. Omura was a vocal opponent of the mass eviction and incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast during World War II. He wrote editorials pointing out the unconstitutionality of the United States style concentration camps and chastised Japanese American leaders, who advocated a policy of government cooperation. He supported the draft resistance movement when the government began drafting men from out of the camps. For taking these stands, Omura's professional and personal suffered, and he was written out of history until the redress movement began during the 1980s. The thirteen years of Omura's life will be revisited in what is dubbed as his "Return to the Wars" diary by Art Hansen, professor emeritus of history and Asian American Studies at California State University, Fullerton and former director of the university's Lawrence de Graaf Center for Oral and Public History. Hansen edited the diary and provided more than 500 end notes. Omura began this portion of the diary in 1981, when he testified before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in Seattle and ends with his death in Denver in 1994. Stanford University Press has just published an edited volume by Hansen entitled, "Nisei Naysayer: The Memoir of Militant Japanese American Journalist Jimmie Omura." A book signing will be held on Saturday, Aug. 25, from 2:00 pm at the Japanese American National Museum, 100 North Central, Los Angeles, CA 90012. Mori Tanimoto and Hiroshi Kashiwagi

Mori Tanimoto and Hiroshi Kashiwagi

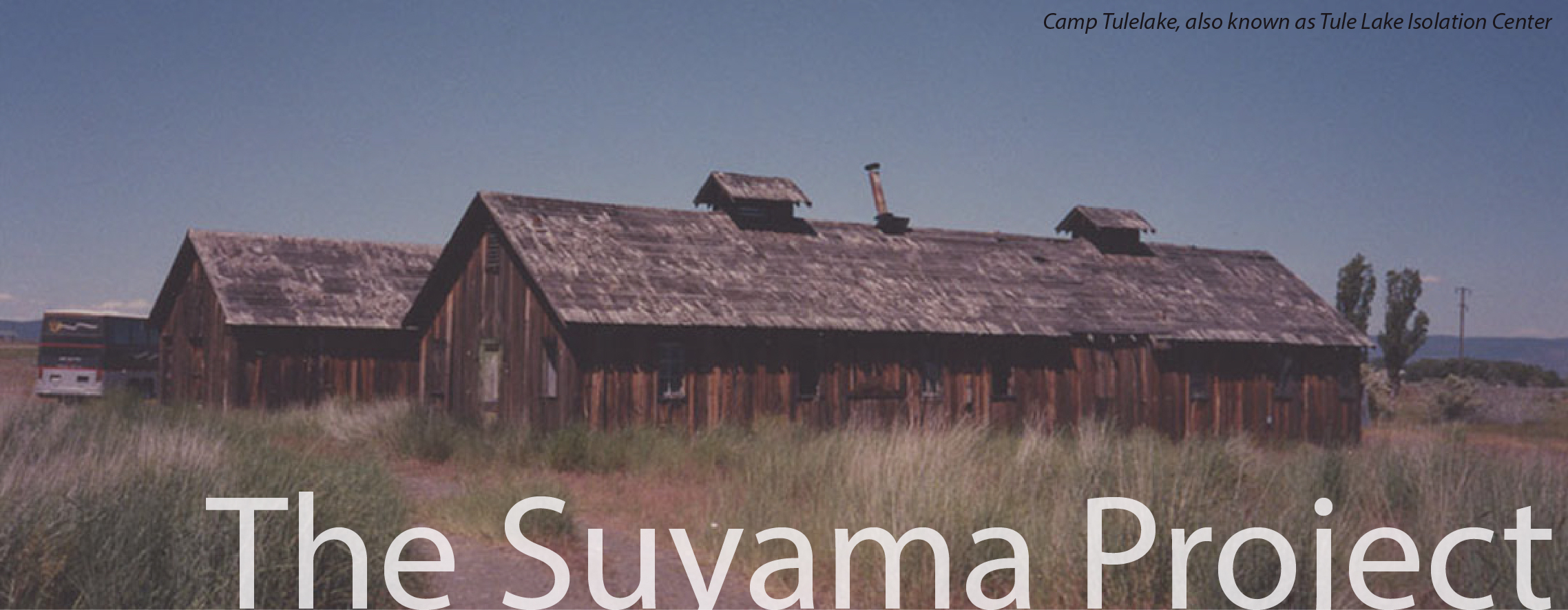

The No-Nos/Tule Lake Discussion, Seattle, WA

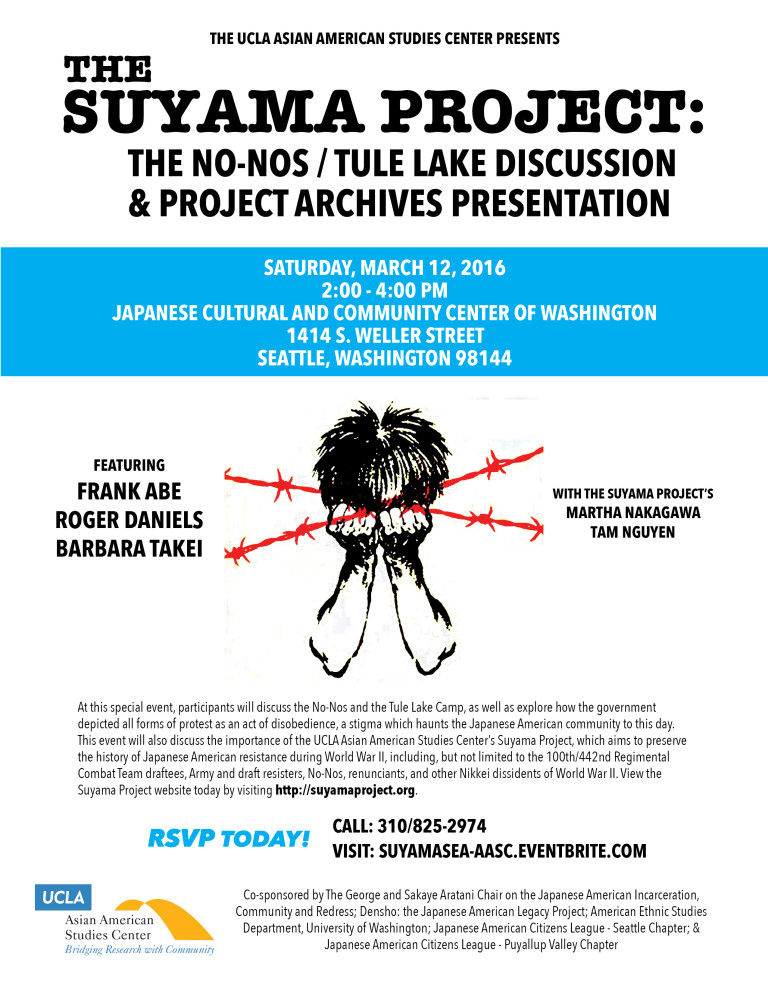

Notorious Tule Lake Segregation Center, Okada's 'No No Boy' Focus of March 12 Public Program in Seattle During wartime, how does a person prove their loyalty to their country? Is it restricted to military service? Or are there other forms of loyalty?

These and other questions of loyalty and patriotism will be discussed at a panel discussion on the World War II Tule Lake Segregation Center and the novel, "No No Boy" by John Okada.

Panelists will include Roger Daniels, University of Cincinnati professor of history emeritus and pioneer scholar in Japanese American history; Barbara Takei, an independent writer/researcher and board member of the Tule Lake Committee; and award-winning filmmaker and journalist Frank Abe.

Daniels and Takei are working on a history of America's worst concentration camp and will share some of their research findings.

Abe, who is compiling new research for a book on John Okada, will share his insights into how Okada took the story of the draft resisters and set it against the places where he grew up in postwar Seattle.

The program will take place on Saturday, March 12, from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington, 1414 South Weller Street in Seattle. A portion of the program will also be devoted to sharing about the UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Eji Suyama Endowment, which strives to preserve the history of Japanese American dissent during World War II.

On hand from UCLA will be David K. Yoo, PhD, Director of the Asian American Studies Center and professor in Asian American Studies.

The program is co-sponsored by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center's Suyama Endowment and the George and Sakaye Aratani Endowed Chair in Japanese American Incarceration, Redress and Community; Densho: the Japanese American Legacy Project; American Ethnic Studies Department, University of Washington; and the Japanese American Citizens League – Seattle Chapter and Puyallup Valley Chapter.

For more info, please contact the UCLA Asian American Studies Center at (310) 825-2974 or RSVP online at: suyamasea-aasc.eventbrite.com No-Nos

On Dec. 10, 1942, the United States government established a heavily guarded citizen isolation center at a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp in Moab, Utah, to imprison U.S. citizens of Japanese descent deemed as troublemakers from the 10 War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps.

The government moved the prisoners to a former boarding school on the Navajo reservation in Leupp, Ariz., as the Moab prison population expanded. The Leupp Citizen Isolation Center opened on April 27, 1943 with 150 soldiers guarding 80 citizens.

The alleged crimes of the men varied from upsetting the WRA camp administrators to participating in protests to arbitrary and uncorroborated accusations made by informants. Some were mistaken identity mix-ups where someone with a similar sounding name was picked up.

These men often received no hearings where they could counter any charges leveled against them. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) had a general leave policy for camp inmates as early as July 20, 1942 due to the pressing need for seasonal agricultural laborers.

Under the WRA's July 20, 1942 leave policy, only American-born inmates who had never lived or studied in Japan were eligible to apply. At this time, however, most Japanese American inmates, imprisoned in the assembly centers, were under the jurisdiction of the Army until November 1942. As a result, all applicants who filled out a WRA leave form were examined by the Army, which more often than not, rejected the requests for leave.

On October 1, 1942, a more liberal leave policy was formulated. By this time, most Japanese Americans were under the jurisdiction of the WRA since they'd been transferred to WRA camps.

However, few inmates were allowed to leave the WRA camps during the first few months of camp operation since the WRA's employment division, which was responsible for the leave program, was understaffed with inexperienced workers.

By the winter of 1942, the government opened seven field offices in the Inter-Mountain region to encourage Japanese American inmates to apply for seasonal leave to help farmers in need of laborers.

To further promote the leave of Japanese Americans from the WRA camps, the government opened a relocation office in Chicago in January 4, 1943. This was followed by other offices in such places as Cleveland, Minneapolis, Des Moines, Milwaukee, New York and other cities throughout the Midwest and East Coast.

In early 1943, the WRA and the War Department passed out a separate but similarly worded loyalty questionnaire to the inmates in hopes of accelerating the process of moving the Japanese Americans out of the camps and towards the Midwest or East Coast.

By this time, the image of the U.S. as a leading democratic country was tarnished as a result of imprisoning its own citizens of Japanese descent into camps. To counter this, the War Department proposed the formation of a segregated Japanese American combat unit for propaganda purposes.

At the same time, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) petitioned President Roosevelt to reinstate the draft for Japanese Americans so as to allow them to prove their loyalty to the U.S. A year earlier in June 1942, Japanese Americans were declared unfit for military service and were no longer being inducted into the armed forces.

As a result, the War Department proposed having Japanese American men of draft age answer a questionnaire to determine their loyalty and their willingness to serve in the military.

The WRA concluded that the War Department's questionnaire plan was also an ideal way to separate alleged "loyals" from "disloyal" Americans in the camps, and suggested a joint effort, which the War Department supported.

The Japanese American Joint Board (JAJB), which was formed on Jan. 20, 1943, was tasked to coordinate efforts between the WRA and the War Department in identifying alleged "loyal" Japanese Americans for indefinite leave and for employment in war defense industries. The recommendations of the JAJB, however, were not binding on the WRA.

Internally, the JAJB came up with a policy which issued points to Japanese Americans for being in certain "American" organizations such as the Boy Scouts and subtracting points for being associated with certain groups that the government deemed too "Japanesey" such as being a member of a Buddhist church. Additionally, visiting Japan or attending Japanese language school was considered a negative.

The JAJB's point system, however, proved to be too unwieldy, and the JAJB was disbanded after a year.

Meanwhile, the so-called loyalty questionnaire that the War Department passed out in early 1943 was titled "Statement of United States Citizens of Japanese Ancestry," DSS Form 304A and had the seal of the Selective Service System affixed on it. This form was passed out to Japanese American men of draft age in the camps, those living outside of the West Coast exclusion zone and those, who had either volunteered or been drafted before the U.S. military stopped inducting Japanese Americans in June 1942. Answering this questionnaire was voluntary.

The WRA utilized the War Department's form as a guideline and came up with Form WRA-126 Rev., titled "Application for Leave Clearance." This was given to all Japanese Americans over the age of 17 in the camps. Answering this was compulsory.

Those who answered the WRA questionnaire to the government's satisfaction became eligible to leave the camps and resettle in areas outside of the West Coast exclusion zone.

Japanese American males, who had filled out an Army questionnaire, were given a short WRA form, also titled, "Application for Leave Clearance."

However, the lack of basic information and the poor wording on the questionnaires had the opposite affect than what the two agencies had hoped for.

Questions 27 and 28 proved to be the most controversial, and they were later revised on the WRA form.

The Army form read: Question 27 — "Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?"

Question 28 — "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and foreswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?"

Issues arose whether answering "yes" to question 27 meant a Japanese American was volunteering for the Army.

Many found question 28 the most insulting since a "yes" answer implied that the respondent had once sworn allegiance to the Japanese Emperor.

On the WRA forms handed out to Issei males, question 27 asked whether the respondent "will be willing to volunteer for the Army Nurse Corp or the WAAC (Women's Army Auxiliary Corp)."

Moreover, question 28 placed the Issei in a no-win situation. Since the Issei, were, by law, ineligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens, they would become stateless if they answered "yes" but face the possibility of deportation if they answered "no."

After the Issei started protesting, question 28 was later altered to read: "Will you swear to abide by the laws of the United States and take no action which would in any way interfere with the war effort of the United States?"

Despite the poorly worded questions, the government considered a "no" answer to both questions 27 and 28 as a sign of disloyalty. Additionally, leaving either space blank or answering them with a "yes-if" conditional clause were considered equivalent to a "no" answer. These inmates became known as the "no nos," and due to government propaganda, they were perceived to be "disloyal" Americans, a stigma that persists today.

Subsequent oral history interviews and scholarly research have uncovered various reasons an inmate became a "no no." These range from a respondent's desire to protest removal and imprisonment to an attempt to keep the family unit together.

Since Tule Lake had the largest number of inmates who had refused to register for the questionnaire, this camp was selected to become a Segregation Center where the “no nos†would be imprisoned.

Approximately 9,000 inmates from other WRA camps were shipped to the Tule Lake Segregation Center in the fall of 1943 in what was most likely their third uprooting (once from their home, second from the assembly centers and third to the Segregation Center).

Another 6,000 "original" Tuleans chose to remain in the Segregation Center to avoid the hassle of yet another forced move.

Not surprisingly, Tule Lake became overcrowded, and inmates faced food shortages and unsanitary living conditions.

As a result, the government stopped shipping "no nos" from other camps after Tule Lake reached a peak population of more than 18,000.

To guard what the government viewed as dangerous "disloyals," the military police was increased to 1,000 men, and the Army engineers surrounded the camp with an eight-foot wire mesh fence, which was topped off with barbed wires sloping inwards.

The overcrowding and tense relationship between the inmates and the administration led to unrest and protests, and the Army entered Tule Lake with tanks on Nov. 4, 1943 and declared martial law. The camp did not revert to civilian control until Jan. 15, 1944.

The citizen isolation center was quietly shut down on Dec 2, 1943, after Leupp Director Paul G. Robertson traveled to Washington D.C. and reported abuses documented by Francis S. Frederick, chief of internal security at Moab and Leupp.

The government had planned to close down Leupp in October 1943 and transfer the prisoners to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, but due to the unrest at Tule Lake, the government delayed the shutdown until December.

Once transferred to Tule Lake, most of the prisoners were placed into the Tule Lake stockade before being released into the general Tule Lake population. For More Information:Muller, Eric L. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II. University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

United States Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority. Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers. 1946 U.S. Government Printing Office.

United States Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority. The Relocation Program, 1946 U.S. Government Printing Office. |

|||||||||||||||||||||