Remembering K.W. Lee, "Godfather of Asian American Journalism" and Champion of the Underdog (1928-2025)

Julie Ha & Sojin Kim

K.W. Lee, an award-winning investigative reporter, editor, and civil rights advocate who inspired and mentored generations of journalists and community leaders, died March 8, in Sacramento at age 96.

The first Korean immigrant to work as a mainstream newspaper reporter in the continental United States, Lee often said his coverage spanned the "Jim Crow South to the Yellow Peril West." From the 1950s through the 1980s, he reported for the Kingsport Times-News in Tennessee, The Charleston Gazette in West Virginia, and The Sacramento Union in California.

Lee's over half-century career embodied the journalistic ideal of "comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable" and earned him more than four dozen journalism awards.

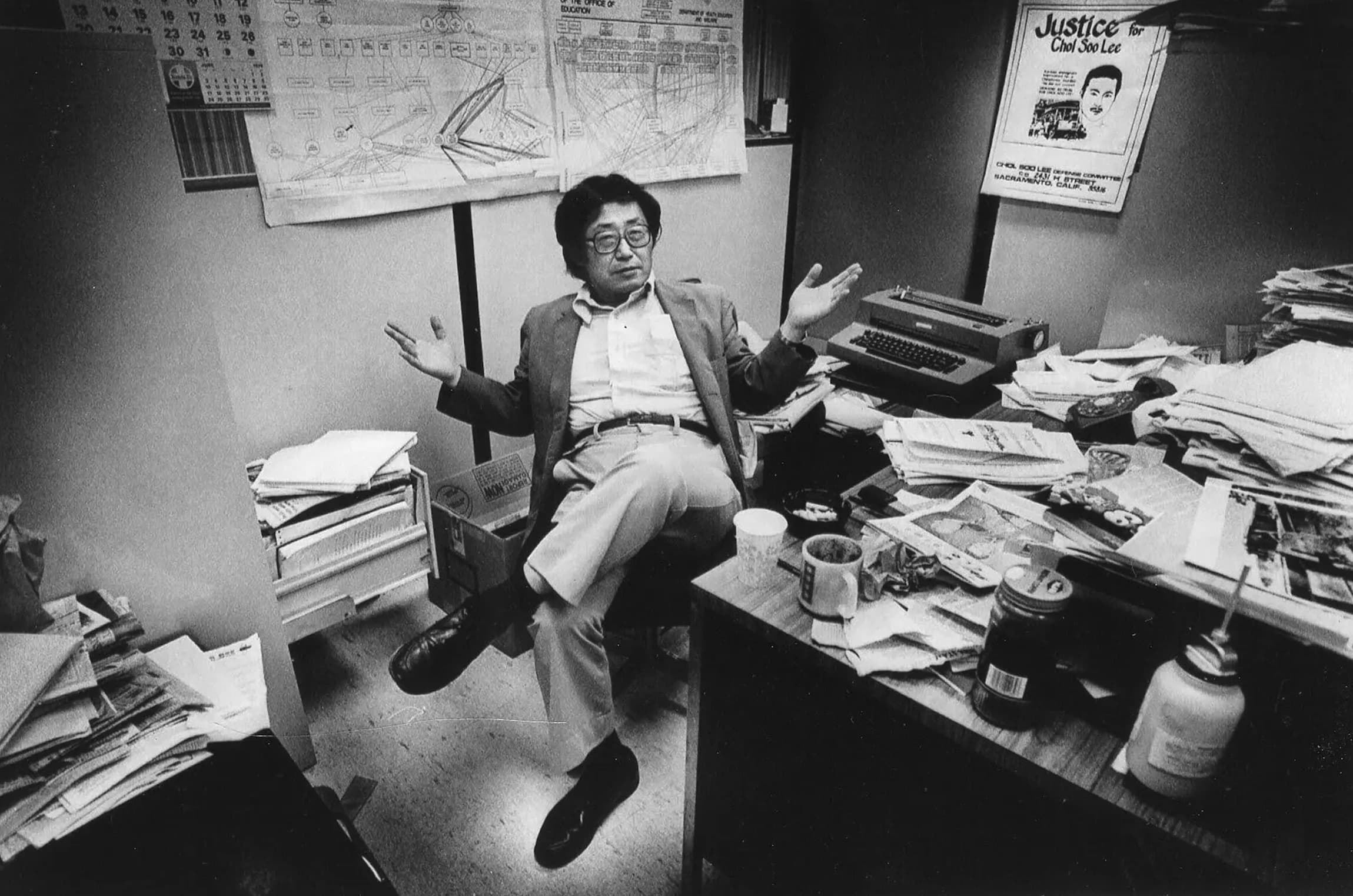

In Sacramento, Lee pursued one of the most important stories of his life. Over nearly six years in the 1970s and '80s, he wrote 120 articles about Chol Soo Lee, a Korean American wrongfully convicted of a 1973 murder and sentenced to life in prison. Lee's coverage inspired one of the first pan-Asian American social justice movements, leading to Chol Soo Lee's acquittal and eventual freedom. The 1989 film True Believer, starring James Woods and Robert Downey, Jr., was loosely based on the case, but completely omitted the journalist and Asian American community's role.

Known as "the godfather of Asian American journalism," Lee was the first recipient of the Asian American Journalists Association's Lifetime Achievement Award and the first Asian American journalist to receive the Free Spirit Award from the Freedom Forum, a nonprofit dedicated to the First Amendment. Inspired by the Chol Soo Lee case, he also helmed two Korean American newspapers in Los Angeles that aimed to bring out the untold stories of this emerging, yet largely invisible, ethnic community.

"He lived to investigate — and expose — injustice throughout society and government," said friend and former newspaper colleague Steve Chanecka. "In my view, K.W. was the most unknown giant in journalism. A complex man, the world was his family, and he taught so much to so many."

Mr. Lee in 2022 with a photo of Chol Soo Lee, the Korean immigrant convicted of murder whose cause he championed in more than 100 articles. He was acquitted at a retrial in 1982. (Hyungwon Kang via Associated Press)

Kyung Won Lee was born June 1, 1928, in Kaesong, in what is now North Korea, and immigrated to the United States in 1950. He studied journalism at West Virginia University and University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, with dreams of applying the principles of a free press in his newly independent homeland. When Cold War instability and repression in Korea quashed these plans, Lee set down roots in the U.S.

As a reporter in Tennessee in 1956, Lee adopted the byline "K.W. Lee." The name led to some surprises when he showed up to assignments. By 1958, he was in West Virginia. Working the weekend police beat, he would hound an emergency room nurse at Charleston General Hospital, Peggy Flowers, for details on victims of accidents and knife fights. One rainy day, she accepted a ride home from him, and their love story began.

"At the risk of sounding like an old sentimental fool, she was my America, in body and soul, who came to the rescue of an exile, providing him with a normal, happy home and a new career in the new world," Lee said of his wife, in a 2011 interview. Two of their three children were born in West Virginia.

Through the 1960s, Lee covered race and poverty. "His work on the Charleston Gazette back in its glory days was exemplary and impactful," said Gibbs Kinderman, a longtime local activist. "He fit right into what was one of the crusading newspapers of its day." For one series, Lee lived for four days with families in the grim hollows of Appalachia. It was there he found American nobility, he said, noting how the families offered him their food even as they lived hand to mouth.

Huey Perry, director of the Mingo County Economic Opportunity Commission in West Virginia in the 1960s, recalled how Lee exposed election fraud that had robbed coal miners and local residents of their votes and led to federal indictments of Mingo County officials. "For the first time, there was hope," Perry said. "The day K.W. Lee left for California, the people wept

Lee was recruited in 1970 by the Sacramento Union to be its chief investigative reporter. Described by his city editor as a "heat-seeking missile," he uncovered threats to public safety from nuclear power plants and exposed exorbitant pensions that state lawmakers were giving themselves. A Union radio ad boasted of his feats: "K.W. Lee ... digging, probing, tackling the bureaucracy, infiltrating the unknown!"

Then Lee learned about Chol Soo Lee. "It was just by the grace of God I have eluded the fate that fell on him," K.W. Lee said in a 1994 interview. "The institutions, the media, and law enforcement, [and] the judicial system have continued to remain ignorant and insensitive. And that's why I felt ... it was my calling to make some small dent in that wall of ignorance and insensitivity."

Ranko Yamada, a leader in the movement to free Chol Soo Lee, praised the "genius in his writing" that made a complex case easier to understand, and the depth of his compassion. Lee's articles, she said, made Chol Soo Lee — who would spend a total of 10 years in California prisons, including on death row — a real person. "And not just a real person that you read about, but somebody like in your own family or, 'It could be me.' "

The story of the former death row inmate was told anew in the 2022 Emmy Award-winning documentary "Free Chol Soo Lee," co-directed by one of K.W. Lee's former interns, Julie Ha. The film highlighted the crucial roles of the reporter and the Asian American community. Lee watched it over and over. "Seeing Chol Soo on his TV screen gave him comfort," Ha said, “and knowing Chol Soo Lee's truth was released to the world, moving people yet again — across borders, language and culture — brought him great peace.”

KW rocks his truth

on a Noah's Ark

on the insurgent sea of Reality

with a hundred other hungry jostling animals

Noble species of

the past century:

Journalists vs. Paper Tigers

Editors vs. Equivocators

Writers vs. worshippers

but the truth is that journalists may be a doomed species

in the cacophony of capitalists & media cronyism

Yet, one word can change

A place, a direction, forever.

Nanjing. Gwangju.

Basra. Saigon. Soweto.

Tiananmen. Ramallah. L.A.

Charge. Change.

You. Not you. Here. There.

Justice. Injustice. Human.

Inhuman. Truth. Lies. Tell.

Struggle and Write. Here and Now.

Tell. Tell. Tell.

—Russell C. Leong

The case awakened what K.W. Lee called his "latent Korean identity," inspiring him to co-found the English-language Koreatown Weekly and later edit the Korea Times English Edition. Published in Los Angeles, the papers aimed to tell the stories of Korean Americans in their "full human context, warts and all," a signature phrase of his.

"K.W. urged us of the pressing need for communities to produce their own storytellers," said Sojin Kim, a curator at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. "He wasn't simply a witness to history. He was a gloves-off-for-the-underdog changemaker."

Sophia Kim was one of those storytellers. She worked with Lee as a former staff writer for Koreatown Weekly and the Korea Times English Edition, and remembered him as a hero, mentor, and surrogate father. "K.W. was such an important person to so many people," Kim said, noting his impact was felt not just on journalists. "He nurtured and inspired practically four generations of journalists, community leaders and social activists."

Amid national coverage of tensions between Korean American business owners and their Black customers, the Korea Times English Edition documented hundreds of stories of Korean merchants trying to live as "good neighbors." Lee traded editorials with a local African American newspaper, the Los Angeles Sentinel, as both papers called for calm and bridge building.

Then, on April 29, 1992, a jury acquitted the white police officers who had been caught on video beating an unarmed Black motorist named Rodney King. The civil unrest that followed saw deliberate targeting of Korean-run businesses. At the time, Lee was hospitalized with a failing liver, but he edited news copy from his bed and penned a thundering editorial calling for justice.

"K.W. Lee [was] a civil rights advocate even before the term was known to Korean America," said Angela Oh, an attorney, ordained Zen Buddhist priest, and race relations expert. "The choice to work as a member of the media and to walk in two worlds — actually even more — made him an invaluable bridge of understanding as marginal communities in this country emerged from invisibility."

Oh added that Lee had "a keen intuition that led him to stories that shed light on corruption in politics, injustice in the legal system, and the need for everyday people to be seen. His was a journey that was grander than grand in every possible way, and his life force will be felt for generations to come."

In retirement, Lee remained a powerful truth-telling voice, writing commentaries, lecturing at universities, including at UCLA, giving inspirational talks at community events and mentoring the next generation.

The fruits of his labor are many.

K.W. Lee reunites with his former Korea Times English Edition staff, mentees and friends at a Feb. 22, 2020, gathering in Yorba Linda, California. First row, left to right: Do Kim, Karen Umemoto, K.W. Lee, and Russell Leong. Back row, left to right: Julie Ha, Chris Kwon, Mindy Yoo, Sophia Kim, Kay Hwangbo, Dexter Kim, Richard Fruto, and Peter Park.

Richard Kim, a professor of Asian American Studies at UC Davis, said Lee changed his life. "He was exacting, demanding, and uncompromising — the larger-than-life character we all know," said Kim, who felt compelled by Lee to share the largely forgotten story of Chol Soo Lee with new audiences. He worked closely with K.W. and Chol Soo for years to produce Freedom Without Justice: The Prison Memoirs of Chol Soo Lee, published in 2017. "He made me a better person and the world a better place with his indefatigable sense of what he believed is right, compassionate, and just."

Members of his former staff at the Korea Times English Edition paid tribute to Lee's brand of community journalism in the book, Saigu: Korean and Asian American Journalists Writing Truth to Power, published by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

One longtime mentee, Do Kim, a Los Angeles civil rights attorney, founded The K.W. Lee Center for Leadership, a nonprofit that nurtures truth, justice and community consciousness in high school and college students. "He used his gift as a passionate journalist to right wrongs and to fight for the unseen, unheard, and forgotten among us," Kim said. In training youth leaders armed with Lee's spirit, the center will carry on that legacy of "fighting for the underdogs."

Survivors of Lee include his children, Shane (Sandee) Lee, Sonia (Victor) Cook, and Diana (Alan) Regan; six grandchildren, Jacob Lee (Alicia), Jared Lee (Ellie), Hanah Cook, Jackson Cook, Lukas Regan, and Layla Regan; and three great-grandchildren, Orion Lee, Altair Lee and Artemis Lee. His beloved wife, Peggy, preceded him in death.

Public "Day of Remembrance" events to honor K.W. Lee's life are being planned for Los Angeles and Northern California. In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to The K.W. Lee Center for Leadership.

These images were shared with the UCLA Asian American Studies Center for the purpose of this in memoriam message. Out of respect to the owners of the images, please do not copy, share, or distribute them.