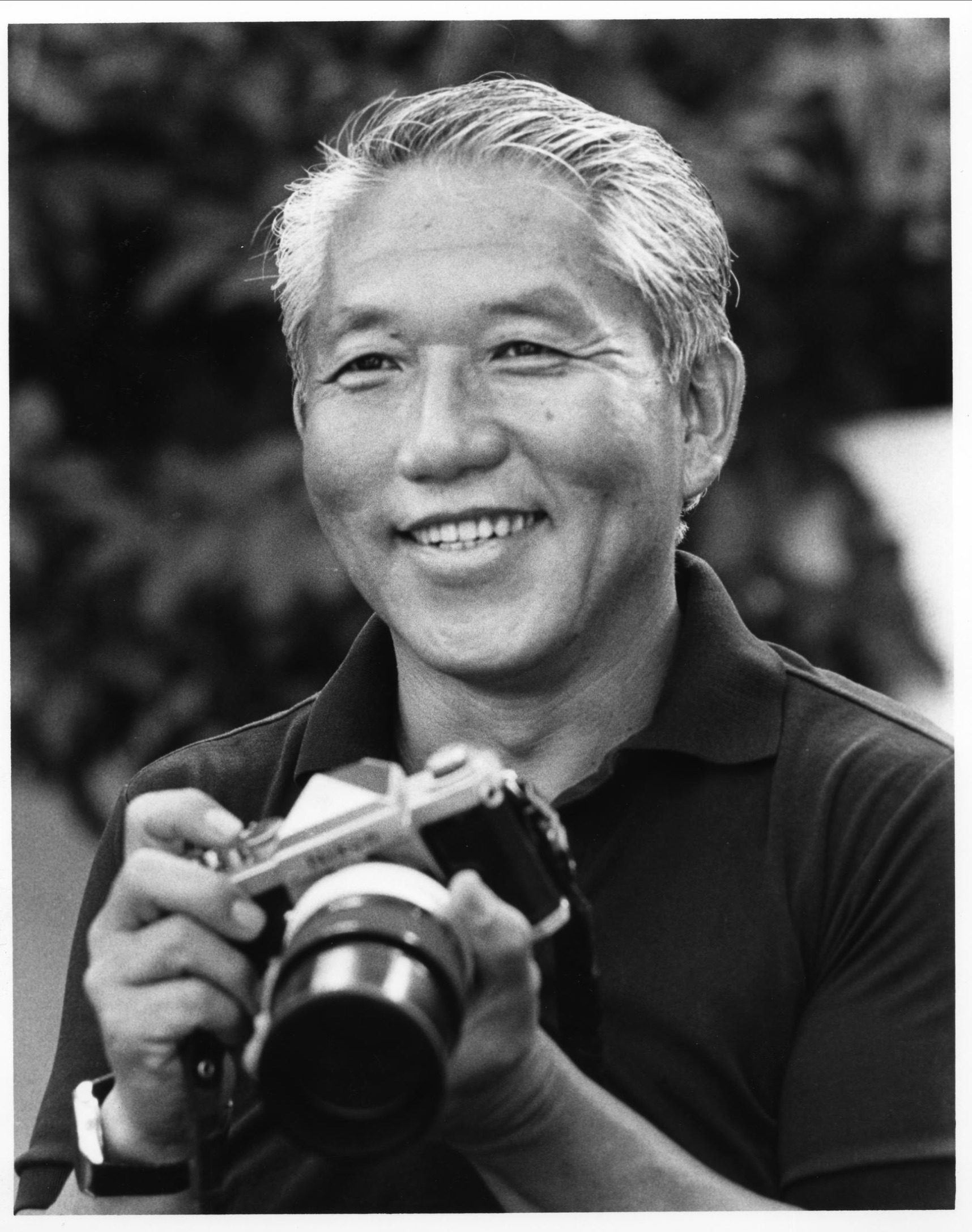

Remembering Bob Nakamura (1936-2025)

"Godfather of Asian American Media"

By Renee Tajima-Peña

The visual eloquence of Bob Nakamura's work draws you into a landscape of memory and stories untold. Films like Wataridori: Birds of Passage, Bob's 1974 profile of his Issei father George, conjures a humanity I recognized in the day to day, in my own ojisan gardening in the backyard, in the pages of my mother's photo albums. For Japanese Americans of my generation, these images may have coursed through our hearts, but they were otherwise enforced secrets never to be projected in the public's eye.

Until Bob conjured our world onto the frame.

Wataridori wasn't my first introduction to Bob's films. That would be the classic documentary Manzanar (1971), now a part of the National Film Registry. I was just a kid when I went to a screening at the Japanese Cultural Institute in Pasadena. This was a time when, outside of Hollywood movies at the theater, no one I knew went to "screenings" and certainly, the concept of an Asian American film director seemed as far-fetched as being a first draft pick in the NBA. Eddie Wong and Bob Nakamura were there to show their UCLA thesis films Wong Sing Saang and Manzanar, Bob's documentary about the concentration camp where he spent years of his childhood. If Wataridori gave life to the simple majesty of our everyday, Manzanar was visible evidence of a monumental travesty of justice that imprisoned our families and imperiled our trust in democracy.

Manzanar hit hard. Only a few years before my grade school teacher had exclaimed to the class that my mother and grandmother were lying about the Japanese American concentration camps. She insisted nothing like that could ever happen in America. Manzanar cast a light on her lies and the erasure of a history that was only a generation past. That was about to change. In the pantheon of truthtellers who compelled America to know our story, Bob emerged as one of our original griots of the screen.

And for half a century he never stopped. With films such as Looking Like the Enemy, Something Strong Within, Toyo Miyatake: Infinite Shades of Gray, Fool's Dance and Hito Hata: Raise the Banner, the first scripted feature of the burgeoning Asian American independent film movement, he laid the foundation for what would come next. Bob was an essential force in creating that movement, beginning during the early 1970s when he was a student in the trailblazing affirmative action program at UCLA's film school, Ethno-Communications.

Bob had arrived at UCLA a quintessential native of a Los Angeles shaped by racism and redlining, born in the Venice neighborhood and raised on the streets of Virgil. Trained at the Art Center College of Design, by 1970 he had a successful career as a commercial photographer, owned a sports car, and had what would seem like a dream life for a post-war Japanese American guy. But an unease was stirring within Bob, within Asian America and within communities of color restless to seize the time. At the UCLA film school, the Ethno-Communications Program was borne from the demands for racial diversity and equity in admissions fueled by student filmmakers like Charles Burnett, Betty Chen, Moctesuma Esparza, Haile Gerima and more. Ethno-Communications unleashed a culture quake — the LA Rebellion of Black cinema, a new generation of indigenous and Latino filmmakers, and a groundbreaking genre of West Coast Asian American filmmaking that Bob would help propel for a half century.

He emerged from UCLA a director and a maverick. In 1970, Bob and fellow students Eddie Wong, Duane Kubo and Alan Ohashi, founded Visual Communications (VC) which still stands strong as the oldest Asian American media arts non-profit in the country. It would be the first of Bob's many firsts. In 1971 VC created a 3-dimensional photographic installation that told the story of the Japanese American World War II incarceration, the first exhibit of its kind at a time when that history was all but erased from the national memory.

Professor Robert Nakamura at his retirement celebration, 2012

Bob became a UCLA professor of film in 1987 and Asian American Studies in 1994, where in 1996 he reprised Ethno-Communications as a teaching program and creative research center. Over the years he nurtured generations of Asian American film talent: Akira Boch, Eurie Chung, John Esaki, Evan Leong, Justin Lin, Ali Wong to name a few. He also found time to serve as Associate Director of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center alongside the legendary center director, the late Don Nakanishi. In 1997 Bob and his partner in life and filmmaking, Karen Ishizuka, co-founded the Frank H. Watase Media Arts Center at the Japanese American National Museum, which became the single most prolific source of films about the Nikkei experience.

Bob and Karen, Karen and Bob. A prolific producing team, a love story, and parents to Thai and award-winning filmmaker Tad, grandma and grandpa to Thai and David Checel's children Mina and Gus, and Tad and Cindy Sangalang's kids Prince and Malaya. In many ways the Nakamura-Ishizukas have been the beating heart of Los Angeles' Japanese American community. Theirs is a glorious extended family, whether related by blood or not, but bound by art, activism, history, love. You think the Met Gala is a big deal? That's nothing compared to a Nakamura-Ishizuka film premiere with exuberant crowds filling the 800+ seat Aratani Theater in Little Tokyo.

Tad's captivating feature documentary Third Act, which premiered at Sundance this year, is the culmination of the vast and stunning body of work that began with Bob's documentary, Manzanar and lives today through Tad's directorial vision. He filmed Third Act, a biography of Bob's life and career, at a time when Parkinson's disease was taking a physical toll on Bob, even while his creativity — and humor — never seemed to waver. It is an unforgettable film, at once a personal documentary and an evocation of the collective memory of a community as it is becoming.

The standing ovations started at Sundance, and in May Third Act came full circle to a sold-out house at the Aratani as a part of Visual Communications' Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival (LAAPFF). With his health declining, everyone was surprised that Bob made it to the Sundance premiere in the Park City winter. Months later, even getting across town to the LAAPFF screening was a valiant effort. But he wasn't going to miss it. Nothing could have been a more perfect homecoming for Bob: Back in Little Tokyo 55-years after launching Visual Communications, his remarkable life of film and activism on screen, his family and crew on stage, surrounded by the embrace of a community that so deeply, dearly loves him.

So many people wanted to see the Third Act that VC scheduled an encore screening the next day. It was another sold-out show. And Bob wasn't going to miss that one either. He came back for more.

We lost a giant on the night of June 10, 2025. Our consummate storyteller, our griot of the screen, teacher and friend. According to Tad, Bob died as he lived: "He passed peacefully at home. The way he wanted to."

Our deepest condolences go out to Bob's family, loved ones and friends. Rest in power and peace. A Celebration of Life event is forthcoming to honor Bob's life and legacy. We will share more details shortly.

These images were shared with the UCLA Asian American Studies Center for the purpose of this in memoriam message.

Out of respect to the owners of the images, please do not copy, share, or distribute them.